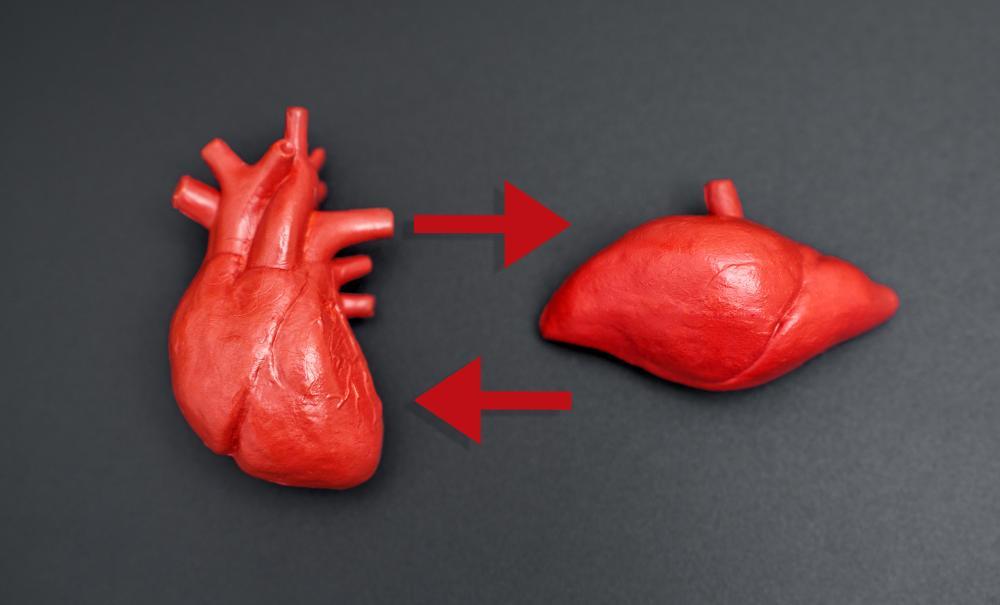

Study finds link between fatty liver and heart disease risk in people with HIV

People living longer with HIV face new, chronic health threats, including steatotic liver disease, also known as fatty liver, and heart disease.

People living longer with HIV face new, chronic health threats, including steatotic liver disease, also known as fatty liver, and heart disease.

A new study from eight U.S. medical centers found that metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, or MASLD, increases the risk of heart disease in adults with HIV.

The condition, once known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, develops when fat builds up in the liver along with metabolic problems like high blood pressure, diabetes, or obesity. The researchers also looked at a related condition called MetALD, which occurs when people with MASLD also use alcohol moderately.

Both forms of liver disease are becoming more common as people with HIV live longer, thanks to antiretroviral therapy. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in 2021, more than 40% of the people in the United States with HIV were at least 55 years old. A person diagnosed with HIV at age 20 would be expected to live into their early 70s if they received effective antiretroviral therapy. This means that people live longer, making them likely to experience chronic conditions such as liver and heart disease.

The study, led by first author Richard Sterling, M.D., the chief clinical officer for the Institute, were published online by the American Journal of Preventive Cardiology.

Heart Risk on the Rise

People with HIV are nearly twice as likely to develop cardiovascular disease as those without the virus. The higher risk is linked not only to traditional factors such as smoking and cholesterol, but also to ongoing inflammation and immune system changes caused by HIV itself.

The research team wanted to learn how these liver problems might add to heart risk, and whether moderate drinking changes that risk.

How the Study Was Done

Nearly 1,000 adults living with HIV took part in the study. They were treated at centers such as VCU, Duke University, Johns Hopkins University, and the University of California, San Diego. All were on HIV medication and had undetectable viral loads. People with hepatitis B or C, or existing heart disease, were not included.

Researchers measured liver fat using a FibroScan, which uses sound waves to assess liver stiffness and fat buildup. They also checked blood pressure, cholesterol and blood sugar, and recorded smoking and alcohol habits.

Participants were grouped into three categories:

- No SLD: normal liver fat levels

- MASLD: fatty liver with at least one metabolic risk factor

- MetALD: fatty liver with at least one metabolic risk factor plus moderate drinking

Of the 991 people in the study, half had no liver disease, 40% had MASLD, and 9% had MetALD. The average age was 52, and about three out of four were men. Half identified as Black, and one in five were Hispanic.

Those with MASLD were more likely to have diabetes, high blood pressure, or high triglycerides, all conditions that raise heart risk. They also had higher body mass index scores and lower levels of “good” HDL cholesterol.

Nearly all participants had at least one risk factor for metabolic disease. Among those with MASLD or MetALD, almost everyone had two or more.

The researchers compared several ways to estimate heart risk, including the long-used Framingham and ASCVD scores and a newer tool from the American Heart Association called the PREVENT calculator. The PREVENT model includes extra details about kidney function and blood sugar to better assess overall health.

People with MASLD had higher heart disease risk across nearly all scoring methods. The PREVENT calculator showed the biggest differences, finding higher 10-year risks for total heart disease, atherosclerosis, and heart failure among those with MASLD.

In contrast, people with MetALD, those who drank moderately, had heart risk scores similar to participants without liver disease. Researchers said higher HDL levels in the MetALD group may partly explain that result.

Why It Matters

The findings show that fatty liver disease tied to metabolic issues may play a key role in raising heart risk for people with HIV, even when alcohol use is limited.

These results highlight the need to screen for liver disease and heart risk factors as part of HIV care. The newer PREVENT score may give doctors a clearer picture than older tools.

Next Steps

The study’s strength lies in its large, diverse group of participants, drawn from across the country. However, because the study looked at data from a single point in time, researchers cannot yet say whether liver disease causes higher heart risk directly. They plan to continue following participants to track future heart events such as heart attacks or strokes.

The team also plans to compare PREVENT scores to heart imaging tests that can directly measure plaque buildup in arteries.