New clues in saliva and blood may help predict need for hospital stays in liver patients

By A.J. Hostetler, Communications Director

Stravitz-Sanyal Institute for Liver Disease and Metabolic Health

Researchers from the U.S. and Canada have discovered that saliva and blood may offer powerful new clues to help predict whether people with liver disease will need to go to the hospital.

Researchers from the U.S. and Canada have discovered that saliva and blood may offer powerful new clues to help predict whether people with liver disease will need to go to the hospital.

This new study, published in the journal Hepatology, was led by Jasmohan Bajaj, M.D., who is with the VCU Stravitz-Sanyal Institute for Liver Disease and Metabolic Health and the Richmond VA Medical Center, representing a consortium called NACSELD (www.nacseld.org). It involved scientists from 10 medical centers across North America who followed outpatients with cirrhosis.

The goal of the study was to figure out which patients might end up in the hospital within six months. Cirrhosis is a common cause of hospitalization, but predicting exactly who will get worse and need care is challenging.

Doctors often rely on clinical scores, such as the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), to measure liver function. But those scores alone are not always enough. This new approach may help clinicians better understand each patient’s unique risks.

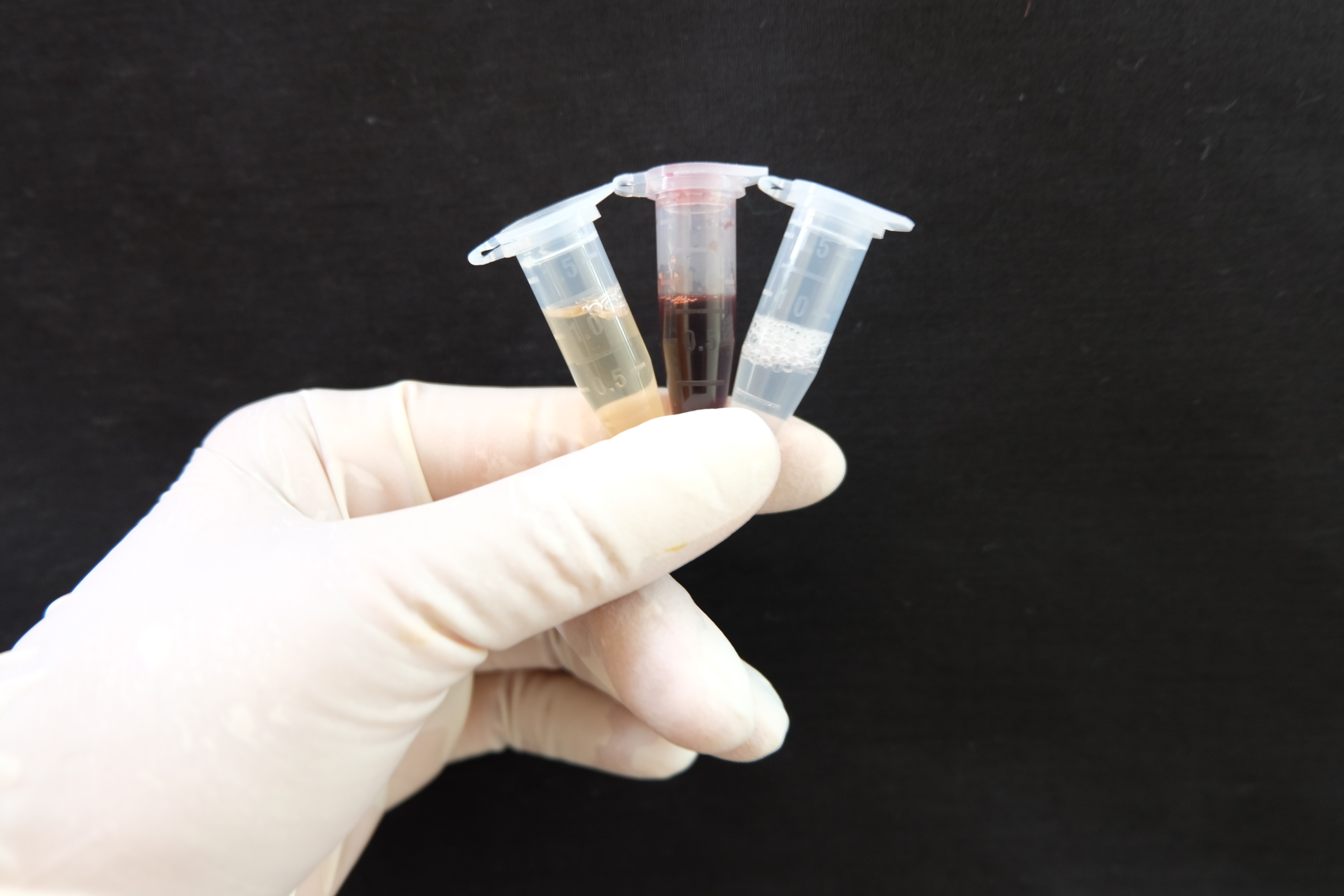

This new research looked beyond typical blood tests and examined "multi-omic" data, in which data from multiple fields (such as genomics, proteomics and metabolomics) are combined to gain a more comprehensive understanding. In this study, they collected data on the bacteria found in patients’ mouths and the chemicals in their blood.

The study enrolled 565 people with cirrhosis who were not actively drinking alcohol or had already been successfully treated for hepatitis C. Their average age was about 60 and nearly 70 percent were men. The leading causes of their liver disease were alcohol use, metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease and past hepatitis C infection.

By the end of six months, 163 patients, about 1 in 3, had been hospitalized. Most of these hospital visits were related to liver problems.

When researchers looked at the patients’ saliva, they found clear differences between those who went to the hospital and those who did not. Patients who were hospitalized had less variety in their mouth bacteria.

They also had more pathobionts, types of bacteria that can lead to disease under certain conditions. These included: streptococcus, treponema, and members of the enterococcaceae family. In contrast, those who stayed out of the hospital had more friendly bacteria, such as veillonella, prevotella, haemophilus and lachnospiraceae.

“This tells us that oral health may be more closely tied to liver health than we thought,” Bajaj said. “Your mouth could be giving early warning signs about what’s happening in your body.”

The study also examined the small molecules in patients' blood, known as metabolites. These included compounds made by gut bacteria, such as phenyllactate, indoles, and secondary bile acids, as well as others linked to the body’s metabolism of choline and polyamines.

Using advanced computer tools, the researchers were able to find clear patterns in these molecules that separated patients who were hospitalized in the next 6 months from those who did not.

When doctors combined the data, they could more accurately predict who was at risk for being hospitalized.

The study used a method called random forest analysis, a type of machine learning that sorts through complex data to find patterns. The researchers found that while clinical data such as MELD scores, hemoglobin levels and albumin remained the strongest predictors, adding information from the saliva and blood made predictions even better.

“This is like adding more pieces to a puzzle,” Bajaj said. “Each type of data helps fill in the full picture of the patient’s health.”

The study shows the value of looking at the whole patient, not just their liver, but also their mouth, gut and blood.

“Hospitalizations are hard on patients and expensive for the health system,” Bajaj said. “If we can better predict who’s at risk, we can act earlier to keep people healthier and at home.”

The team included VCU’s Jawaid Shaw, M.D., Brian Bush and Leroy Thacker, Ph.D.