A genetic clue to liver disease: What PNPLA3 tells us about risk

It’s well known that lifestyle factors like diet, obesity, and alcohol use can increase the risk of liver disease. But scientists are learning that a single gene known as PNPLA3 can also play a critical role. For millions of people, this small genetic variation may quietly shape their liver health.

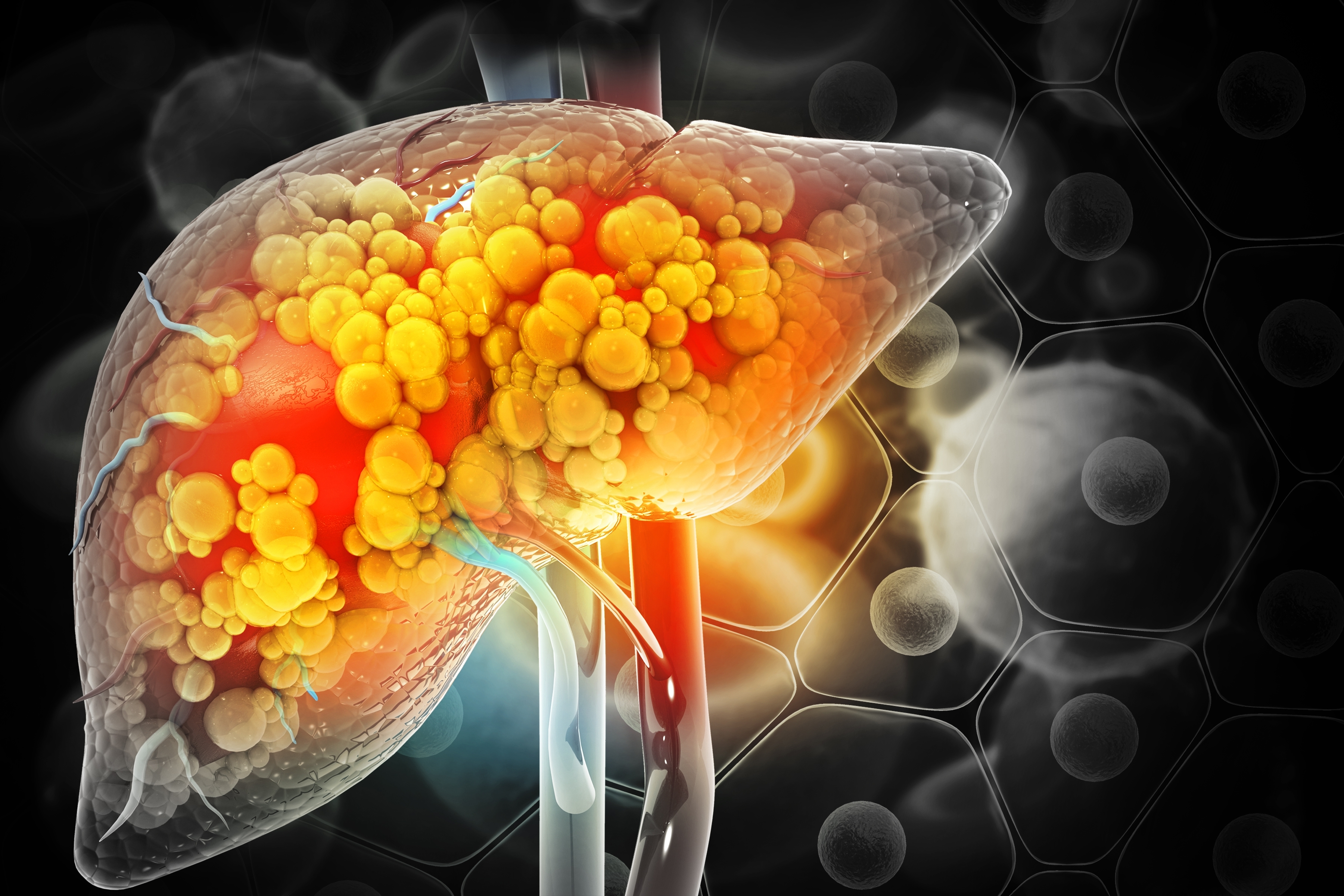

First identified in large genetic studies, PNPLA3 has become a focal point in understanding how and why fat builds up in the liver, a condition known as fatty liver disease, or steatotic liver disease. The gene makes a protein involved in processing fat inside liver cells. Most people carry a version that functions normally. But others carry a slight alteration, the PNPLA3-148M variant, in which a single-letter switch in the gene’s code is a key driver of fat-related liver disease, including more severe forms like cirrhosis and liver cancer.

In the journal Liver International, Institute Director Arun Sanyal and colleagues from New York City and North Carolina assess the strengths and limitations of in vitro and in vivo models, as well as the challenges arising from species differences in PNPLA3 expression and function between human and murine systems.

The hidden risk

Fatty liver disease includes a spectrum of liver conditions, starting with the simple fat accumulation (steatosis), which may cause no symptoms. If it progresses to steatohepatitis, it can cause liver inflammation and damage. Left unchecked, this can lead to cirrhosis (scarring of the liver) and hepatocellular carcinoma, the most common form of liver cancer.

While poor diet and alcohol use are familiar culprits, individuals with the PNPLA3-148M gene variant face a higher risk of developing these conditions. The researchers say that raises important questions: How exactly does this gene affect liver function? And, how can we better study it?

What the science shows

Instead of helping the liver break down fats, the PNPLA3-148M variant seems to trap fat in the liver. It may also interfere with other proteins responsible for managing fat storage and removal, further tipping the balance toward unhealthy fat buildup.

Studying the gene in mice hasn’t clarified matters much. Mice without the PNPLA3 gene don’t automatically develop fatty liver, suggesting that the gene variant’s story is more complex. However, when researchers introduce the human PNPLA3-148M variant into mice, the animals do show signs of liver fat accumulation, which may bring us closer to understanding the variant’s effects in humans.

Studying PNPLA3 isn’t simple, as human and mouse livers don’t function the same way. As a result, many researchers are now shifting to more human-like models, including human liver cells grown in labs and mice which carry human genes or even human liver tissue.

These models enable scientists to test not only how the gene works but also how new drugs might target it. Promising therapies aimed at blocking or modifying PNPLA3-148M are already in early development. If successful, these drugs could offer new hope for people at genetic risk of liver disease.

The PNPLA3-148M variant is found across many populations, but it’s especially common in people of Hispanic and East Asian descent. Understanding this distribution is crucial — not just for science, but for public health. Genetic screening could one day help identify individuals at higher risk and guide personalized prevention strategies.

The bottom line

The discovery of PNPLA3-148M has shifted how researchers think about liver disease, reminding researchers that while a single gene variant isn’t destiny, it can be a powerful factor, especially when combined with other risks.

This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA027327) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (P01HL160472 and R01HL131093).