Common heart risk tools miss the mark for people with MASLD

By A.J. Hostetler, Communications Director

Stravitz-Sanyal Institute for Liver Disease and Metabolic Health

Doctors may overlook serious heart risks in people with a common liver condition, according to a new study involving more than 1,000 patients across the United States.

Doctors may overlook serious heart risks in people with a common liver condition, according to a new study involving more than 1,000 patients across the United States.

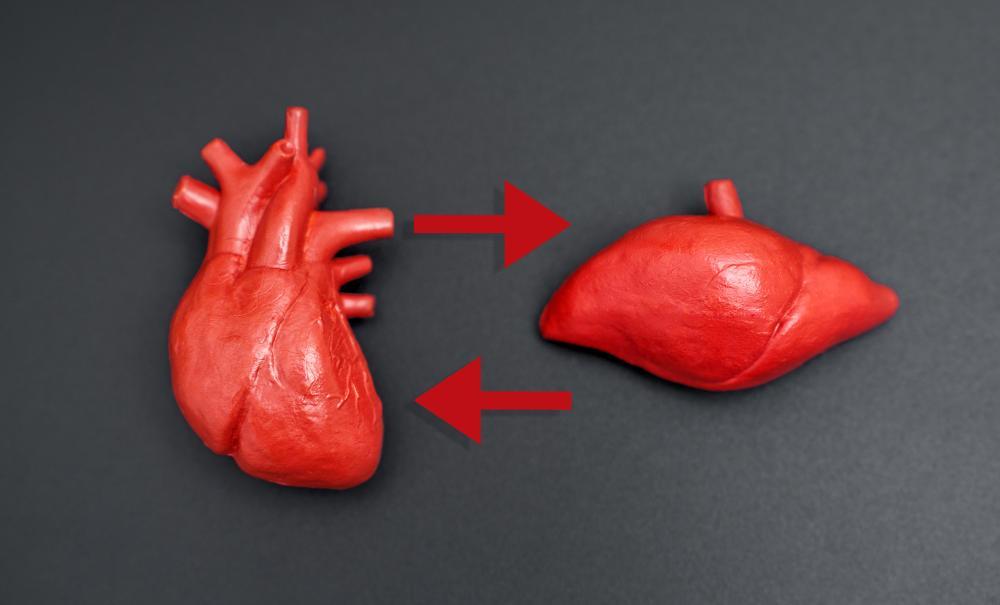

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease occurs when excess fat builds up in the liver. MASLD includes a range of disease stages, from mild fat buildup, to inflammation (known as MASH), and eventually to liver scarring.

MASH contributes to heart disease by promoting the buildup of excess fats, such as cholesterol and triglycerides, in the liver, as well as producing chemicals that inflame other tissues, such as blood vessels.

While liver damage is a major concern, the number one cause of death in MASLD patients, prior to cirrhosis, is heart disease, not liver failure. But the tools doctors typically use to predict heart risk do not appear to work well for these patients, according to new research posted online by the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Physicians turn to special calculators, age, cholesterol, blood pressure and smoking habits, to estimate a person’s chance of having a heart problem in the next five or 10 years. Three of the most common tools are the Framingham Risk Score, the Pooled Cohort Equation, and the American Heart Association’s PREVENT model. But it’s been unresolved about whether they work well for patients who have liver disease.

The new study, for which Institute Director Arun Sanyal, M.D., was senior author, explores this question. Researchers used information from the TARGET-NASH study, which includes patients in the United States with MASLD, and focused on adults who were at least 30 years old. The investigators tested how well the three heart risk tools predicted real heart problems, such as heart attacks, in this group.

Common tools miss the mark

When the study looked at people with different levels of liver disease, none of the tools performed well. In fact, the Framingham score only showed a very weak ability to predict risk in people with MASH.

The researchers also found that the risk calculators often got it wrong. In patients predicted to be at the highest risk, the tools often overestimated the danger. But in those predicted to be at the lowest risk, the tools underestimated how likely heart problems would be.

That is especially troubling, researchers said, because people with mild liver disease are often the ones not receiving treatment to reduce heart risk.

In fact, only 18 percent of people with MASLD were taking a statin to help reduce the risk of heart attacks. In comparison, 31 percent of those with MASH and 35 percent of patients with cirrhosis were on statins.

The problem may be that patients with milder liver disease simply do not appear as sick, so doctors and patients alike may not feel the urgency to treat other risks. Yet, even with mild disease, the study found more heart events than expected.

Newer tools may do better

Other studies have looked at different ways to measure heart risk in people with liver disease. One tool used in the United Kingdom, for example, did a better job of predicting heart problems than traditional American tools. It included factors like mean platelet volume, a measure found in common blood tests, rather than just focusing on cholesterol and age.

Newer versions of risk calculators are also being developed and tested. These may include body mass index and remove race as a factor, which some experts say may help make the tools more accurate and fairer.

Better treatment could help both heart and liver

In addition to using better risk calculators, researchers say that directly treating liver disease could also improve heart health.

In clinical trials, one such drug, resmetirom, which is approved by the FDA to treat MASH and moderate liver scarring, also lowered levels of LDL, or “bad” cholesterol, by up to 16 percent.

Very few patients in the study were taking a GLP-1 receptor agonist approved to treat diabetes and obesity and also shown to protect the heart. But they are expensive and not always covered by insurance, which may be why they are used so rarely in MASLD patients.

In addition, Sanyal says, tests that measure calcium deposits in the coronary arteries may be another important tool to assess patients with MASLD for risk of coronary disease. Diastolic dysfunction and cardiac electrical disturbances are also important causes of heart disease in those with MASLD and more advanced fibrosis severity is linked to greater diastolic dysfunction.

“Given the importance of cardiac outcomes in this population, it is imperative that assessments of these aspects are integrated into the routine assessment of patients with MASLD/MASH,” Sanyal said.

A need for change

The new findings echo earlier research showing that many people with risk factors for heart disease are not getting treatments that could help them. For people with MASLD, this gap in care could have deadly consequences.

The study’s authors say that doctors may need to rethink how they evaluate heart risk in these patients, especially those with mild liver disease. Physicians should not wait for liver disease to worsen before treating heart risk. Instead, they should be proactive, using a more complete picture of the patient’s health to guide care.