Global differences in the management of alcohol-associated hepatitis

An international team of researchers revealed that treatment for alcohol-associated hepatitis varies widely around the world, underscoring the need for standardized care across all aspects of managing the disease.

An international team of researchers revealed that treatment for alcohol-associated hepatitis varies widely around the world, underscoring the need for standardized care across all aspects of managing the disease.

In The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology the team, led by corresponding author Juan Pablo Arab, M.D., of the Stravitz-Sanyal Institute for Liver Disease and Metabolic Health, examined global variability in treatment, including the use of corticosteroids and access to liver transplantation.

Alcohol-associated hepatitis (AAH) is a serious liver condition in people who drink heavily over a long period. It often leads to symptoms like yellowing of the skin (jaundice) and feeling very weak or sick. AAH has a high risk of death in the short term, and there are few effective treatments.

The main focus of care is supportive, such as ensuring proper nutrition and treating infections. Steroids have been used since the 1970s to treat AAH, but they don't always work well. In recent years, early liver transplantation has been suggested as a way to improve survival, but this option isn't available everywhere.

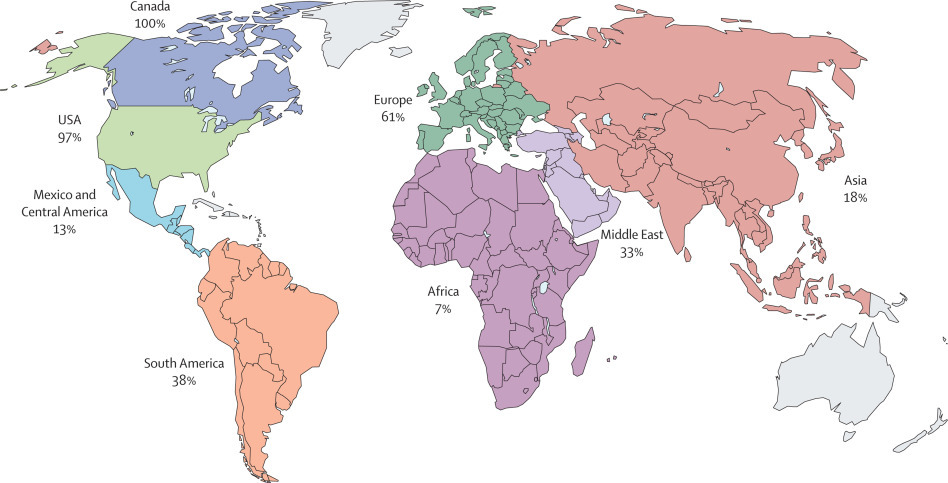

A survey of liver specialists worldwide found different approaches to treating AAH. About 59% of the 373 doctors surveyed routinely used steroids, but this varied depending on the region and whether the doctor worked at a liver transplant center. Steroid use was more common in North America and Europe and at transplant centers. Access to early liver transplantation also varied significantly, with better availability in the United States, Canada, and Europe compared to Africa and Asia. How doctors decide if a patient is a candidate for a transplant also varies by region.

Even though treating the underlying alcohol use disorder (AUD) can help prevent and slow liver disease, few doctors in the survey routinely prescribed medication to treat it. Only 38% recommended or prescribed AUD medications at discharge. This may be due to the lack of awareness, slow adoption of new treatments, or not enough strong research supporting their use, the researchers noted.

Given the disparities in treatment, the researchers said there is a clear need for more consistent care and better education to improve outcomes for patients with this condition.