Preventing, treating serious infections in liver patients

Two recent studies have raised questions about how doctors should prevent a serious infection that affects people with liver disease. This infection, called spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, happens when bacteria infect the fluid in the belly. Doctors often give patients antibiotics to prevent the infection from coming back after they've had it once.

The first study, published in The Lancet Gastroenterology and Hepatology, looked at how infections impact patients hospitalized with severe liver disease, or cirrhosis, around the world. Infections are a major problem for hospital patients with cirrhosis, especially in lower-income countries. The study, led by the CLEARED Consortium, examined 4,238 patients from 98 hospitals across 26 countries between November 2021 and December 2022.

Researchers discovered that about 32% of these patients had infections when they were admitted to the hospital. Infections were much more common in lower-income countries, with nearly 42% of patients affected, compared to 29% in wealthier nations. The most common types of infections were spontaneous bacterial peritonitis -- a bacterial infection in the abdomen, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections.

Patients with infections had worse outcomes. Nearly 22% of infected patients either died in the hospital or were transferred to hospice care, compared to just 8% of those without infections. The study also found that infections were often caused by drug-resistant bacteria, with a 40% rate of resistance. This problem was especially high in upper-middle-income countries, making it harder to treat infections effectively.

The types of bacteria varied by region, with Gram-negative bacteria, such as *Escherichia coli* and *Klebsiella pneumoniae*, being the most common. Unfortunately, the rate of culture-positive tests—where doctors can identify the exact bacteria causing the infection—was low, especially in Africa and mainland China. This makes it difficult to select the right antibiotics, leading to inappropriate treatments.

The study highlights the need for better infection control and treatment options for patients with cirrhosis, especially in lower-income regions where resources are limited. Addressing these challenges on a global scale could help reduce the risk of death from infections in these vulnerable patients.

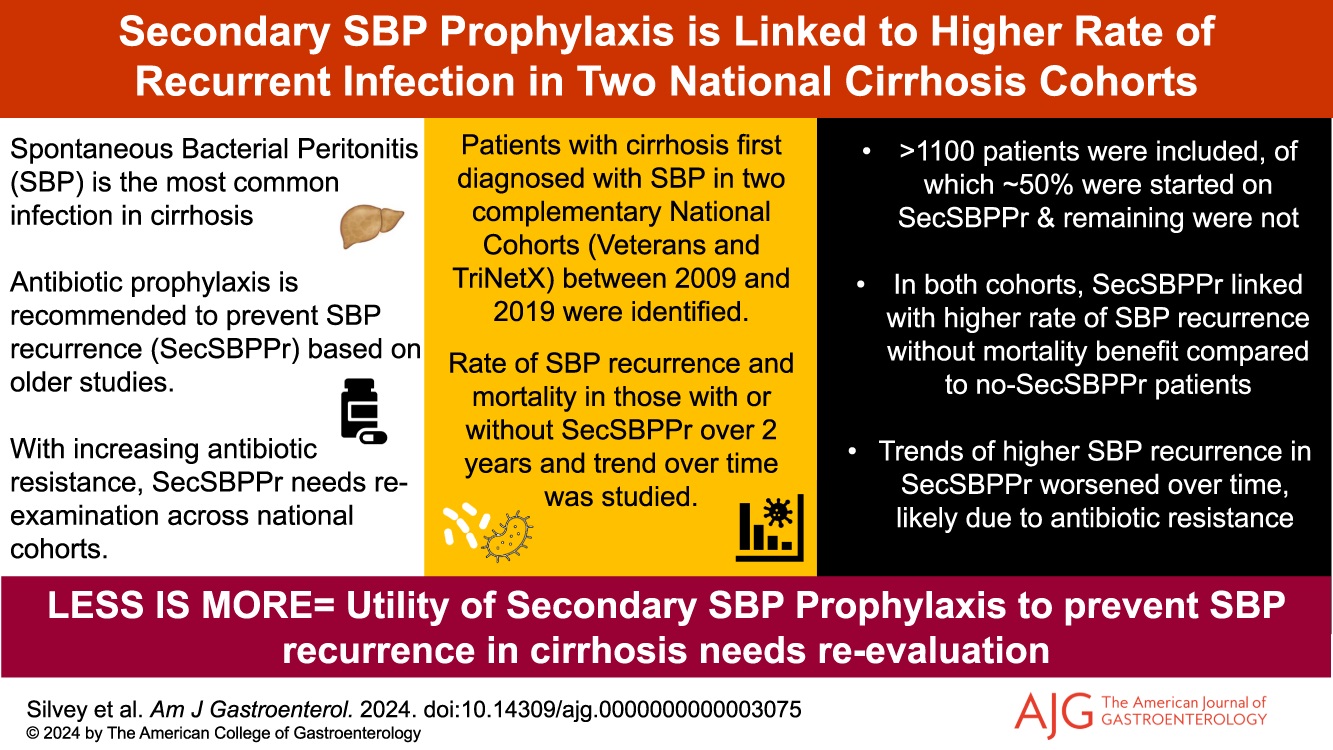

The second study, which recently appeared in the American Journal of Gastroenterology, investigated whether using antibiotics to prevent the recurrence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is effective. The study looked at over 11,000 patients and found that those who were given antibiotics after their first infection were actually more likely to get the infection again. In fact, the risk of recurrence increased by 63-68% compared to patients who weren’t given antibiotics after their first infection.

The study also found that patients on antibiotics were more likely to develop resistance to fluoroquinolones, a type of antibiotic often used to treat this infection. However, despite the increased risk of the infection returning and the growing antibiotic resistance, these treatments didn’t help patients live longer. The researchers observed this pattern over both 6-month and 2-year follow-up periods.

Because of these findings, the researchers suggest that doctors should reconsider using antibiotics routinely for all patients to prevent this infection. Instead, they may need to focus on a more personalized approach, especially given the rise in antibiotic resistance.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge